Kaleb Horton

Writing can be beautiful.

I always thought of Kaleb Horton as one of my favorite living writers. His stuff is the kind of thing that legions of guys imagine they’d write before finally penning the Great American Novel: lonely, a dusty road, a greasy diner, smoking, country music. With anybody else, it’d be ridiculous, a caricature of the American West. With him, it was just his world. He’d come from nothing and was still there, talking to aspiring rappers in parking lots in Pacoima and his uncle in Bakersfield (Merle Haggard was discovering Netflix, a sure sign that his time was almost up). A singular talent sending dispatches to the rest of us. If the guy ever wrote a bad sentence, I haven’t read it (and I’m not even going into his photos, which were themselves perfect stories). He died on Friday so I guess now he’s one of my favorite dead writers.

Luke O’Neil wrote a great remembrance of him. I didn’t know Kaleb well, we just knew each other forever in the way that all of us who are addicted to the internet know each other, so I can’t say much about him other than that I’d always thought he was astoundingly cool and when I finally met him at a Chinese restaurant in some strip mall in Los Angeles, I was ecstatic. Before my first trip out there, thinking that if I was exposed to the sun long enough I’d stop being depressed (this didn’t work: depression in LA is actually worse, you feel like nature is laughing at you, as I’m sure he could’ve warned me), I asked him for tips. He wrote me a guide with notes like “break into the Hollywood Bowl overlook by scaling a small rockface next to the fence.”

Like a character from an earlier time, too cool for today. As it turns out, that was true: he couldn’t make a living at writing, not in a world where being a genius makes you unemployable. I hadn’t realized just how much trouble he was having until I read Luke’s piece. Plenty of great writers have to do other work, that’s not news, but talking with friends over the weekend, everyone sounded mystified by it. People won’t pay this guy to write? He should’ve been a household name, but the world doesn’t run on “should.” “The last magazine writer” indeed: might as well call it and write an obituary for writing itself instead. He said he wanted to write a novel “about the dust bowl that takes place over the duration of a man’s life and begins in Oklahoma and ends in Bakersfield and opens and closes with the line ‘can you swing a hammer?’” Somebody should’ve strapped him to a chair and covered his room and board until it was done.

I’ve been sending friends my favorites among his work so I figured I might as well use this blog to compile them. That’s another indignity: Kaleb’s writing should be sitting on a bookshelf but instead a lot of it literally cannot be found, gone in the winds of dead links. The stuff he wrote while working at MTV, for example: the site doesn’t exist anymore. His trip to hell in the form of seeing the Entourage movie passed around via the Internet Archive.

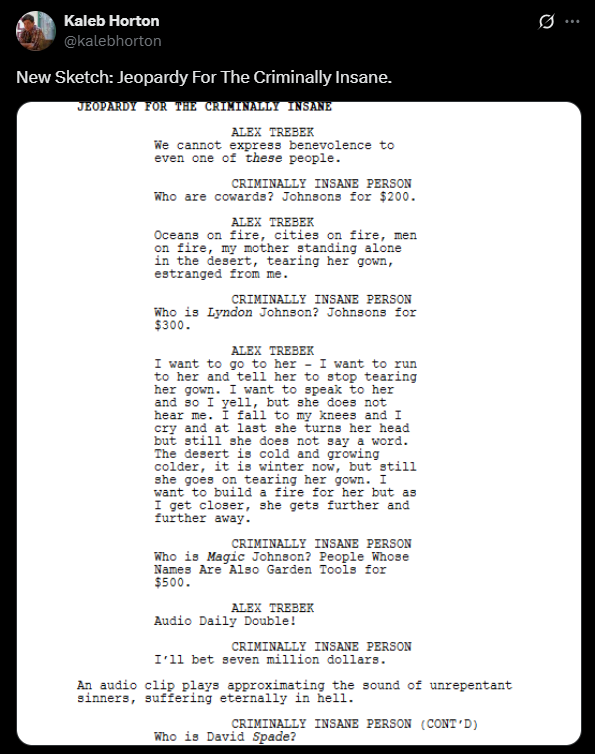

So to save myself time, here’s some of his work. His stuff on dead guys is a genre unto itself: Merle Haggard, Norm MacDonald, John Prine, David Lynch, Shane MacGowan, Bob Newhart, Charles Portis (this one got me to finally read him). Some of these feature his grandpa, one of my favorite of his characters. Here he is running into Merle’s steel guitarist on a reservation where he buys his tobacco, there he is astride his motorcycle, breaking into the town’s high school to see Johnny Cash and Elvis perform (“I ain’t paying no two dollars for a concert”). All of it is funny, which isn’t a surprise if you followed him on social media. The guy had rhythm, the fruit of a lifetime of listening to country music—that makes all writing flow but especially comedy. (No wonder Norm loved him.)

Then there’s his epic on an old crime of the century, a big kidnapping in the little town of Chowchilla. His search for chicken stands in California. His absurdly earnest considerations of Nathan Fielder and Peanuts (“The longest-running meditation on loneliness, defeat, and alienation ever in popular American art.”) I already mentioned Merle Haggard, but his piece on the fellow son of Bakersfield is perfect. The time he saw his heroes Bob Dylan (“a natural troll”) and Willie Nelson (“He’s 91. That’s 350 in country music years.”) and simply could not believe people talked over Dylan like he was a lounge singer (“He did speed and coke. He could die in 30 minutes. This is like seeing Woody Guthrie in 1995. Don’t you care? Don’t you want to see this, whatever it may be?”) Some of it’s on his blog, where his own loneliness, defeat, and alienation seep in, but never in the way everybody else writes—woe is me, here’s a catalogue of complaints. Always art, beautifully rendered.

He told a friend of ours that all he wanted was to be an artisan, and well, he was. One of the best out there. It is a loss to the public that most people have never read him and never will; the people in charge of the media should be summarily fired over such gross incompetence. That overused quote from Stephen Jay Gould—“I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops”—comes to mind with people like Kaleb. Pick an art or science: odds are, the greatest practitioner of it, the biggest talent, is instead doing something else because they need the money. So we mostly get the work of people who had enough of a cushion to do what they wanted. It’s a mass of wealth wasted, an oft-forgotten, incalculable cost of capitalism. A rational society would ensure the truly gifted could devote themselves to their work. The culture suffers for it. Of course, people work at their gifts anyway: always have, always will. Kaleb was one of them.

My mind keeps circling back to the ending of a book I haven’t read in years. Gilead, by Marilynne Robinson. I guess because it makes me happy and it’s pretty.

I’ll pray that you grow up a brave man in a brave country. I will pray you find a way to be useful.

I’ll pray, and then I’ll sleep.

Night, pal.

Thank you Alex. Debbi, his mom showed this to me with tears in her eyes(how could there not be?). Her one wish out of all of this is Kaleb not be forgotten by his peers and fans. All who knew and loved him know he didn’t have a malicious bone in his body. What an injustice.

Never heard of this guy (or you!) until he died and people like you are eulogizing him so evocatively. I’m sorry for your loss, and sorry to lose all of his future writing and living. Any fan of Charles Portis is a friend of mine. Looking forward to reading more of you and him.